The first funeral I ever attended was my grandma’s. She passed away when I was 19. Many would say I was lucky that all my family members and friends had been healthy up to that point, but for me, that first funeral seemed to set off a domino effect. Again and again, I found myself in church pews wearing black or sitting in friends’ dorm rooms as they mourned.

Death had been a topic I avoided, afraid it would infect my loved ones simply by speaking its name. Now I had no choice. Death was in my life, and I had to learn to grieve and mourn — for myself and also with others.

With my grandma’s passing, I knew it was OK to mourn. I sat in the front row at the funeral in the seats marked for family. I received cards from loved ones expressing condolences. I didn’t feel guilty when I cried, and I knew which friends to call for silent drives on deserted South Dakota highways and which friends to call for hugs.

When a dear friend’s loved one passed away, I sat toward the back, focused on showing support for my friend. I didn’t even consider how it was affecting me. But months later, the emotions caught up with me. I found myself suddenly crying or being unusually impatient with others. My unprocessed grief was making itself known, and it wasn’t going to leave until I walked through it. The problem was, I didn’t know how.

Each Journey Is Unique

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, an expert on death and grief, quickly became one of my guides as I attempted to process my loss. I learned while there are stages, grief is not a linear process; it may never be complete. As I read her book “On Grief and Grieving,” I learned that everyone grieves differently.

In my mourning, I had the freedom to dictate how my grief should look. Kübler-Ross writes:

“Your loss and the grief that accompanies it are very personal, different from anyone else’s. Others may share the experience of their losses. They may try to console you in the only way they know. But your loss stands alone in its meaning to you, in its painful uniqueness.”[1]Kübler-Ross, Elisabeth and Kessler, David, “On Grief and Grieving: Finding the Meaning of Grief Through the Five Stages of Loss” (Scribner, 2005), p. 29.

I needed to give myself freedom to feel whatever I was feeling — anger, sadness, regret, resentment, relief, even nothing at all. As I worked through my emotions, I became more aware of what my body was saying, whether it needed more sleep, more alone time, food, or more time with people.

When you grieve, your body and mind are undergoing a lot of stress, both from the pain of your loss as well as the transition of reorienting your life without your loved one. I discovered that instead of feeling guilty because I was more tired than usual, I could give myself grace and needed rest.

Trust That God Is Present

Sometimes we believe, even subconsciously, that if someone is good and works hard, good things should happen to that person. How often have I heard of someone receiving a cancer diagnosis and thought, But she is so nice! Why her? Life is not fair. Loved ones leave this earth too soon, those in their twenties become widows and orphans. We will receive good things we did not work for, such as God’s grace and provision, but we will also suffer losses that we seemingly did not “earn.”

When loss inevitably comes, a natural response is to be angry with God. Like the psalmists and even Christ on the cross, we can cry out to God and yell, voicing the emotional agony He already knows all about.

“I assumed that God was big enough to tolerate my anger and compassionate enough to understand,” writes Jerry Sittser, who lost several immediate family members to a drunk-driving collision. “If God was patient with Job, I reasoned, he would be patient with me too.”[2]Sittser, Jerry, “A Grace Disguised: How the Soul Grows through Loss” (Zondervan, 2004), p. 59.

As I went through a series of unexpected deaths, my journey with grief was filled with a lot of anger and questions as to why God didn’t intervene. I spent nights furiously writing in my journal, letting God know how angry I was. As I did this, my initial anger actually brought me closer to God and opened my heart up to healing.

Supporting Friends Who Grieve

As I went through my own grieving process, I learned firsthand how I could better support friends in their seasons of mourning. At times, I have felt helpless as I watched someone I love feel intense pain, knowing I could not bring back their loved one.

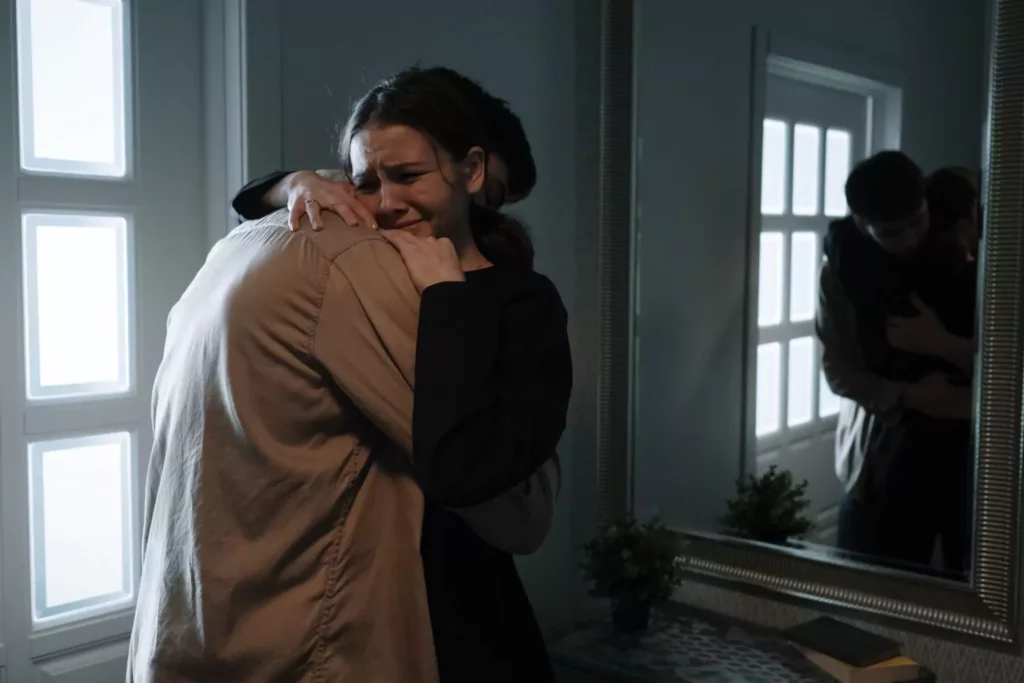

Initially, I tried to offer kind words as a feeble attempt to comfort my friends. Realizing that it wasn’t working, I began sitting with them in silence, sometimes hugging, sometimes side by side. Silence can be uncomfortable and awkward, but my friends wanted to know someone was there without the pressure of conversation. As we sat on my college futon, I could slowly see their shoulders relax and they could begin to breathe again.

After my grandmother died, some friends didn’t know how to relate to me because they were worried they’d say the wrong thing. They wondered if it was OK to be happy around me or talk about their own grandparents. Having friends feel awkward around me only made me feel more isolated.

One way to support friends who are grieving is to let them mourn in ways they need to, even if it gets weird. They may need to be angry, cry in public, or not talk about it at all. Stepping into a friend’s pain without offering quick fixes can help ease the isolation that accompanies loss.

A second way to help is to simply show up. Many people told me, “Let us know if you need anything.” A few actually entered into my grief. A person who is mourning may not know what he or she needs, or they may be hesitant to ask for help.

Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg, who lost her husband unexpectedly, advises,

“The best approach is to really ask people. Say, ‘I know you’re going through something terrible. I’m coming over with dinner tonight. Is that OK?'”[3]Shapiro, Ari, “ ‘Just Show Up’: Sheryl Sandberg On How to Help Someone Who’s Grieving”, NPR Online, April, 25, 2017.

Showing up with meals, cleaning their homes, doing their laundry, calling or texting to regularly check up on them are all tangible ways we can offer support and show love to others during this tough time.

Hope in the Midst of Grief

A sudden, tragic loss drastically changes every aspect of our lives, including some of the hopes we had for our future. The death of a parent or sibling changes what we thought our wedding would look like. Becoming disabled by grief changes the ways we enjoy life.

This is true for the smaller losses as well — remaining single, struggling with infertility, a career not measuring up to expectations. Sittser says:

“Expectations can remain high, as high as they were before the loss, but only if we are willing to change their focus. I can no longer expect to grow old with my spouse … but perhaps I can expect something else that is equally good, only different.”[4]Sittser, “A Grace Disguised”, p. 88.

While the effects of grief and loss may never fully go away, we can still lead full and fulfilling lives. In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus preached that those who mourn are blessed because they will be comforted. (Matthew 5:4) In the moment, grief may feel nothing like a blessing, but we can hold our Savior to His word, trusting that at some point, as we mourn, we will be blessed.

When I felt there would be no relief for my pain, I leaned into His promise that I would be comforted. I know that the tears and grief are temporary. Someday they will give way to joy and praise.

Copyright 2017 Lindsey Boulais. All rights reserved.

References[+]

| ↑1 | Kübler-Ross, Elisabeth and Kessler, David, “On Grief and Grieving: Finding the Meaning of Grief Through the Five Stages of Loss” (Scribner, 2005), p. 29. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Sittser, Jerry, “A Grace Disguised: How the Soul Grows through Loss” (Zondervan, 2004), p. 59. |

| ↑3 | Shapiro, Ari, “ ‘Just Show Up’: Sheryl Sandberg On How to Help Someone Who’s Grieving”, NPR Online, April, 25, 2017. |

| ↑4 | Sittser, “A Grace Disguised”, p. 88. |