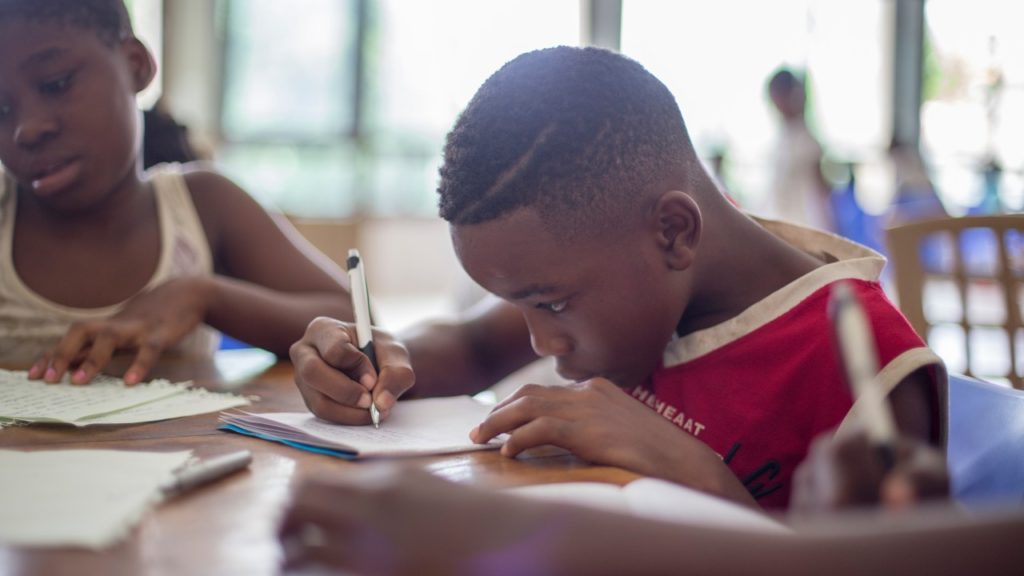

The “first day back at school feeling” was exhilarating as I was prepared to volunteer at our local after-school program. With the coordinator scrambling to find people willing to teach a few hours each week, I had signed up to teach reading and writing to first- and third- graders. This school has been designated as a Title I school, meaning many students attending were disadvantaged and the school received extra funding to assist in specific areas of education. The cafeteria was loud and chaotic as the students scarfed down their bean burritos and fruit cups. I stood in front of my class’s table with the attendance sheet in hand. I inhaled as I read the list and looked at children from a variety of ethnicities — some born here, others having arrived just the month before as refugees — I realized nothing had prepared me for what I was about to experience.

When I was young, my family moved into one of our area’s better school districts, which meant a longer commute for my dad but also the promise of a brighter future for us kids. I grew up with a variety of extracurricular activities, classrooms of reasonable size, an ample number of textbooks, and parents with time to volunteer as fieldtrip chaperones. When funding got tight, our middle-class town voted to increase taxes instead of reducing the school’s budget and letting go of certain faculty members, such as teacher assistants. The school, and, consequently, the students, thrived because of the vast and intricate support system that filled key pieces the school lacked. This support system is critical for the success of a school, but it is a luxury those in low-income communities, like the after-school program I taught at, cannot provide.

The Problems We Face

Those who live in low-income neighborhoods (including urban, suburban and rural areas) receive less academic resources, experience less educational benefits and opportunities, and will learn less than their counterparts in higher-earning areas. Why is this? First, there are the systemic factors: These schools are grossly underfunded, overcrowded, and are lacking basic resources such as guidance counselors, teacher assistants and supplies. Each state is in charge of how they fund their schools. For many, it’s through property taxes. Instead of funding each school according to their need, schools in higher-earning areas automatically receive more funding simply because their neighborhood’s property values are higher.

There are other contributing factors that restrict a child’s learning potential. The Institute of Education Sciences reports that “on average, students in low-income communities are three grade levels behind their peers in affluent communities by the time they are in fourth grade.” And sociologist Donald Hernandez discovered for those children who are not reading proficiently at the end of third grade (which is 82 percent of low-income neighborhoods) are four times more likely to drop out. If they do make it to graduation day, these students have received on average only an eighth-grade level education, disqualifying them from the rigors of collegiate academics. “To put this in context, children from wealthier communities graduate from high school having successfully taken trigonometry or calculus. But the average high school graduate from a school in a low-income community is still unable to solve basic algebra problems,” writes Nicole Baker Fulgham in her book Educating All God’s Children.

It can be easy to place the blame for a child’s lack of educational opportunities on his parents, especially if we don’t know anyone in this situation. Fulgham recalls an experience where she judged the parents of her students in Compton, California for not attending parent-teacher conferences. Reading her students’ life experiences through the lens of her own, she smirks, “After all, at least one of my parents came to every one of my parent-teacher meetings; why couldn’t my students’ families make the same effort?” While Fulgham’s father worked long hours and traveled often, her mother was a stay-at-home parent, leaving space to attend events such as parent-teacher conferences and volunteer during the school day in her daughter’s classroom. On the other hand, the parents (or parent or grandparent for single-caregiver homes) of Fulgham’s students were working multiple jobs for hourly wages with no paid vacation days. Taking time off for a conference meant losing money and, if you are in the working class, there is no wiggle room for a decreased paycheck.

In my own experience working in after-school programs at low-income schools, I heard how several middle schoolers would wake up early to take care of their younger siblings since their parent(s) had to leave for work before the school bus came. An elementary student told me how glad he was when school was back in session because, thanks to the free lunch and breakfast programs, he had three meals a day. Other students share their apartments with family members in order to make their rent, affecting the quality of sleep they receive each night. Most of my students were getting sick more often due to inadequate housing and unaffordable health care.

They showed up every day with more stresses than most children have to (or should) deal with, and we, as a society, are expecting them to learn. It’s like they are being asked to bake a cake but are only given two-thirds of the ingredients and have one arm tied behind their back. When they don’t succeed, their self-worth is shaken and feelings of inferiority creep up through the cracks.

Of the 15 million children who attend low-income schools, more than half will not graduate. These children are 50 percent more likely to live in poverty and 63 percent more likely to be incarcerated. Our society will forfeit an estimated $260,000 in lost earnings, taxes and productivity per student. These students may grow up to fill the soup kitchens our churches staff, attend the clothing drives held in our parking lots or be visited by us in prison. We are left with a choice: assist them now, while they are still in school, or later, when they are unable to thrive in an adult life they weren’t equipped for.

Building Towards a Solution

When Isaiah is prophesying about the expected Messiah, he says those Christ has redeemed “shall build up the ancient ruins; they shall raise up the former devastations; they shall repair the ruined cities. The devastations of many generations.” For decades, our underfunded schools have been barely hanging on, doing the best they can with what little they have, as their buildings dilapidate and their faculties buckle under the stress.

Education inequality affects children of color in greater numbers, specifically those who are black, Latino and Native American. These communities have suffered under generations of oppression, and it continues through the lack of a quality education. As the redeemed, we are called to repent, rise up and repair that which has been devastated, which includes low-income schools.

It is at this crossroads that I, a childless, single woman, find myself with a place to be of service. Singles are more likely to volunteer their time, and there are tangible and needed ways for Christians to get involved in education reform. You can begin by asking the school principals what they need, and then truly listening and finding ways to meet those needs. Your small group could sponsor a teacher, provide financial and emotional support such as purchasing school supplies, blessing them with coffee shop gift cards or inviting them over for dinner, as well as praying for them, their students and their school each time you meet. You could read with a child once a week or teach self-confidence classes.

There are 322,000 churches in America and 98,800 schools. What would it look like if three churches teamed up to adopt a school? How would this change our country?

In the documentary Undivided, a suburban church in Portland, Oregon, adopted a Title I high school. It started with them simply doing a once-a-year deep clean of the school’s building. But slowly, more people began getting involved on a deeper level. One member started a clothing closet in the school, including shoes and hygiene supplies, always asking what they could do and how they could support the school’s vision. One of their members became the assistant football coach, and another helped girls with their self-confidence as they prepped for the school pageant. Since many of the parents worked long hours and were unable or couldn’t afford to attend the girls’ basketball games, the church members, wearing the school’s green and gold, filled the stands. The church began to know the kids’ names and stories, and the kids began to realize the church actually cared for them. The love of God was being expressed in such tangible ways that neither party could walk away unchanged.

Throughout my time at a low-income school, my heart was broken for all my students had to overcome. I also experienced the immense love of God by seeing how much He cares for all of the children. He cares about their spiritual salvation, but He also cares about their home lives, their emotional and social developments, their feelings of worth and purpose. It’s not enough to sing “Red and yellow, black and white, they are precious in His sight” as we allow millions to fall through the cracks. It isn’t enough to simply say “God loves you” to children in low-income communities; we must show them this through our actions and time. Getting involved in low-income schools is one tangible and accessible way we can show each child how precious they are in God’s eyes.

Copyright 2016 Lindsey Boulais. All rights reserved.