Can you imagine the bones of Jesus?

Try, just for a moment, to picture them. Do you suppose they lie in some hidden burial chamber on the outskirts of Jerusalem, just waiting to be excavated? It may not fit your worldview, but to some people it’s the most natural thought in the world. Human beings are born; human beings die, and if you’re a human being in first-century Jerusalem, your bones end up in an ossuary hidden in a burial chamber on the outskirts of the city.

Imagine that the bones of Jesus don’t matter.

Try, just for a moment, to understand the people who live with this assumption. Since Jesus is alive in heaven (they say), it doesn’t matter if His body still lay there on Sunday morning. It doesn’t matter if His flesh turned to dust, if the dry bones were gathered a year later, if an ossuary was scratched with His name. If I don’t believe this, they say, look at 1 Corinthians 15, where Paul writes that we are raised with a spiritual body, not a physical one.

Something feels wrong — but I’m not sure what. I know that the fate of this body matters supremely — but I don’t know why. It is time to do a little excavation of my own.

Make no mistake: if He rose at all

it was as His body;

if the cells’ dissolution did not reverse, the molecules

reknit, the amino acids rekindle,

the Church will fall.[note]John Updike “Seven Stanzas at Easter”[/note]

“The physical resurrection of Jesus is important,” my mentor reminds me, “because Jesus himself asserted it.” Ah yes, the disciples, afraid of a ghost, were reassured that “Ghosts don’t have flesh and bones, as you see I have.”

A concordance search brings me face to face with those disciples, and I discover that they viewed Jesus’ resurrection as the decisive proof of His Sonship, His authority to judge the world, and thus His authority to forgive sins. In the minds of these fishermen who risked their lives to preach about an empty tomb, the Resurrection is absolutely foundational to our salvation.

An empty tomb? The Sadducees had no room in their worldview for resurrection or the afterlife, except as a joke.[note]Matthew 22:23-33[/note] That resurrection might be a Person rather than an event never occurred to the Pharisees, who expected that the soul would someday rejoin the body — but not until the end of time.[note]John 11:23-26[/note] The Greeks and Romans had another view entirely: With the death of the body, the immortal soul was eternally set free. To them, a bodily resurrection must have been about as appealing as Frankenstein’s monster.

But now, says the Apostle Paul, “the firstfruits of them that sleep” has returned from the dead, and He knows the truth about all that God has prepared for us. As it turned out, the truth was something more heavenly — and more earthy — than anyone expected. And so (like Master, like pupil), Paul turns to parable to get things across. “Have you ever noticed how an ordinary seed sprouts into something new?” he asked.

So also is the resurrection of the dead…. It is sown a natural body; it is raised a spiritual body.[note]1 Corinthians 15:44[/note]

But what in the world is a spiritual body? At last, I found my answer, buried in 134 comments at the bottom of a blog post. Dr. Ben Witherington III wrote that the Greek word used in 1 Corinthians 15

… does not describe the material out of which the body is made. ‘Pneumatikon soma’ no more means ‘spiritual body’ (which a Pharisee would see as an oxymoron anyway) than ‘psuchikon soma’ means a body made out of soul. On the contrary, the former means a body empowered by the Holy Spirit and the latter means a body empowered by the natural life breath God gave to humans.[note]Comment # 36[/note]

By now, I have visited the websites of skeptics and apologists, delved into information and misinformation, waded through rumor and rhetoric. I am satisfied that the foundations of my faith are rock-solid, but I am tired. Spiritually and emotionally exhausted. Have you ever tried to breathe steak? Or eat oxygen? Not very satisfying. If it’s irresponsible to live without thinking my faith through, it’s impossible to keep that faith alive without refreshing my heart.

And it is time for me to go on pilgrimage.

The Passion in Israel

Passover

It is the evening of Passover, and oil lamps flicker along the table as a whole roasted lamb makes its grand entrance. We pass heavy pottery cups of wine from hand to hand and dip crackly unleavened bread into shared dishes of ground apple and cinnamon. I watch as a father turns to his son, saying, “You are our firstborn, and tonight would have been our last night together….” He brandishes a fistful of hyssop, a sprig of tiny cuplike leaves, before dipping into a sticky red substance and smearing it on the doorpost.

“Why is this night different from all other nights?” asks a little girl, her hazel eyes sparkling shyly. The answer is already scripted in the Book: “You shall tell your son in that day, saying, ‘It is because of what the Lord did for me when I came out of Egypt.'” Centuries before, God himself had set up this meal as a multi-sensory reminder of His saving power. It’s not surprising that Jesus used it for the same purpose. “This do,” He said, “In remembrance of Me.”

The Garden

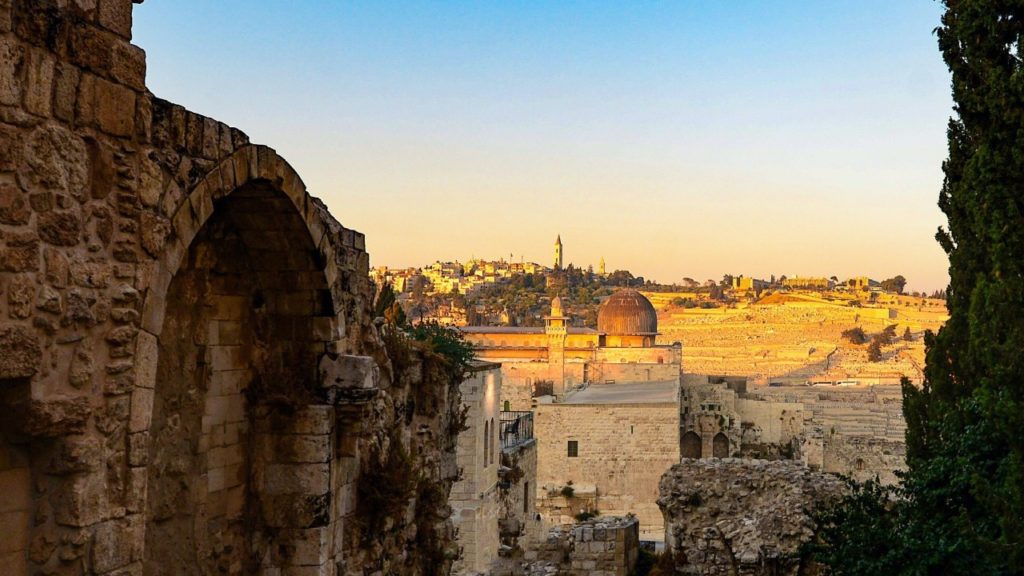

It is the evening of Holy Thursday. As we wind our way through the Old City, we join a stream of Christians making their way toward Gethsemane. And the Church of All Nations is filling fast with pilgrims from all sorts of nations, leaving a crowd perhaps a third again as large to stand outside. I see Arabs, Americans, Asians, Indians, Italians and other Europeans. I see nuns and tourists, priests in brown robes and priests in white, young people, old people, cameramen and children. The atmosphere is hushed, and reverent, the lighting dim. An unseen choir sings quietly to the tune of Handel’s “Largo.” Nearly everyone is standing, blocking all but brief glimpses of the rock outcropping at which Jesus may have prayed His final prayer.

After standing as long as I can, I join the old saints along the back wall, sinking gratefully onto the cold stone floor. When I look up, the people blend with the forest of pillars leading up to the 12-domed roof. There a mosaic tangle of olive branches gleams with occasional touches of gold against a dull blue, star-studded sky. I can imagine that the lone voice chanting is Jesus’ voice at prayer while I, the disciple, battle the demands of my weary body in order to stay awake.

The Jewish people have a tradition that they missed the giving of the Law at Sinai because they fell asleep. Now at every anniversary of that day, they stay awake and study all night. The first disciples missed their opportunity to share Jesus’ last struggle due to sleep, but we modern-day disciples want to learn from them. “Could you not watch with Me one hour?” Jesus pleaded. We want to watch with Him.

At the close of the service, most of the pilgrims retrace Jesus’ next steps. He and his captors would have walked a short distance to the foot of the Mount of Olives, turned left and taken the Tyropean Valley until they reached the Pool of Siloam. Opening a small gate in the city walls, they would have dragged him up a steep, narrow flight of stairs leading to the opulent Upper City area and Caiaphas’ palace. For the modern-day visitors, it is a time to mourn, and to remember. They sit quietly on the stairs in the dark, meditating.

Good Friday

It is Good Friday morning when I sit at the top of those fateful first-century stairs and review the history of the site with Father Giles. I find him chatting with his friend, the cat, whose steel-gray fur matches his master’s hair perfectly. In response to the cat’s hungry complaints, Father Giles remarks, “I didn’t feed him this morning because it’s Good Friday.”

I carelessly left my water bottle at home, but when I grow thirstier and thirstier in the intense spring sunshine, I remember that Jesus hung on the cross in just such heat and experienced greater thirst than mine. That evening, I watch “The Passion of Christ,” struggling not to hide my eyes from the devastation that can be wreaked on one human body.

Saturday

I’ve often wondered how the disciples felt during the three days that Jesus was in the grave. Now I wake in the middle of the night with a feeling of inexplicable heaviness. What happened? Oh yes: Jesus died.

The Tomb

It is very early in the morning on the first day of the week. When I arrive at the Garden Tomb, I am not alone: Scandinavians and Scots, Americans and Aussies, Koreans in warm jackets and Africans in Easter hats are all there too, waking up the birds and the bus station next door with the loudest joyful noise East Jerusalem hears all year.

At first it’s hard to imagine anything so joyful happening at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, traditional site of the Resurrection. But if I meld research and imagination, probing deep underground and back 2,000 years, I reach an abandoned quarry just outside the walls of Jerusalem. From its craggy east wall juts a knob of stone rejected by the builders. Tombs are cut into its west wall, tombs in the distinctive contemporary style, with rows of niches radiating from a vestibule entrance.

I scan lightly over the decades, seeing Jewish believers gathering here until 66 AD, shortly before all Jews were expelled from Jerusalem by the Romans. I see the emperor Hadrian systematically building pagan temples atop holy sites all over Jerusalem, including this one. But look: Not quite 200 years later, Roman Christians are excavating here, moving tons of landfill, stone walls and pavement in order to build a dome named for the supreme event of their faith: Anastasis — “resurrection.”[note]Jerome Murphy-O’Connor: The Holy Land, Oxford University Press, 1997, pp. 45-49.[/note]

When I make my way through the press of people at the door and step into the gloomy interior, I am surprised to hear music coming from deeper inside. It seems that the whole world is here, too, and at the little chapel-within-a-chapel which marks Jesus’ empty grave, an Easter service is going on. Expectant pilgrims press closer and closer, and from the balcony, organ and choir music is rising and expanding inside the great dome of the basilica. I close my eyes, drinking in Handel’s “Largo,” and experiencing that rare moment of joy that comes when you suddenly know you are in the right place at the right time, doing the right thing.

Reflections

But the place I experienced the Resurrection the most vividly is an airplane seat thousands of feet above the Atlantic Ocean. There I was, reading the Gospel story for the first time in Hebrew, my second language. Forced to take it word by word and phrase by phrase, I began experiencing the events in near real time.

Jesus had — His cross. I wouldn’t want my personal pronoun coupled with that word. Would you? Joseph of Arimathea asked for — the body. All God’s greatness reduced to that one pitiful word. And then, at the grave was — a stone — a large stone. Who could move that? When the women ask that question, I am right with them. When the angel brings such preposterous news, I am so with them that I chuckle in disbelief….

Rewind 2,000 years. It’s Passover, and just a few days ago this man named “Salvation” arrived in Jerusalem for the feast. The city is packed with pilgrims from around the world, and as he entered, everyone acclaimed him with the familiar words of the Psalm they were about to read at the Seder meal. “Blessed is He who comes in the name of the Lord! Hoshia na — Save us please, son of David!”

Now it’s after the meal. He’s been praying in his favorite garden on the Mount of Olives, dreading separation from the one he has never been separated from before. He could have just nipped over the other side of the hill and fled to the Judean wilderness, but instead he stays on.[note]Jerome Murphy-O’Connor: The Holy Land, Oxford University Press, 1997, p. 128.[/note]

What’s His response to stealthy arrest? “This is your hour and the powers of darkness.”

The powers of darkness were in for a surprise.

Me, too. I begin to see more clearly than ever before that there are two dimensions to the story. In one realm, Jesus suffers deeply. In the other one, He is God’s select agent on the ultimate rescue mission. This story is about a man who meekly accepts excruciating injustice; it’s also about King Jesus blasting into death and hell, and rocking them to their very foundations!

But now the battle is on in earnest. He’s dragged along, down the mount, across the narrow Kidron valley, through a narrow gate, back into the city, and up a narrow flight of steps. Welcomed to the house of Caiphas with beating. Witness to betrayal as Peter says, “I don’t know the man!” Shown into His room for the night, some 20 feet under.

There He had plenty of time to think over all that He knew was coming:

You have laid me in the lowest pit,

In dark places,

In the deeps.

LORD, why do You cast off my soul?

Why do You hide your face from me?

Lover and friend have You put far from me,

And my acquaintance into darkness.

Shall they that are deceased arise and praise You?

Shall Your lovingkindness be declared in the grave?

The answer is a resounding Yes!

Being put to death in the flesh, but made alive in the spirit … he went and preached unto the spirits in prison. He descended into the lower parts of the earth … [but] when he ascended on high, he led captivity captive.[note]Verses are freely paraphrased. The originals can be found in Psalm 118, Luke 22:53, Psalm 88, Ephesians 4:8, and 1 Peter 3:19.[/note]

And what happened to His body?

It is sown in dishonor; it is raised in glory. It is sown in weakness; it is raised in power. It is sown a natural body; it is raised a body empowered by the Holy Spirit.[note]1 Corinthians 15:44[/note]

And a body empowered by the Holy Spirit was enough to take the disciples’ breath away. That body ate, drank, embraced — and walked through walls and doors. The risen Jesus was so vital that His friends acted nothing like grieving men. Their imagination, which ought to have been painfully fixated on that sepulchural shelf, was fired with telling the preposterously good news.

And preposterous it certainly seemed. Those who did not want to be convinced — weren’t.[note]Luke 16:30-31[/note] But to those who loved Him, Jesus gave all the personalized assurance of His resurrection they needed. He will do no less for us.

Copyright 2008 Elisabeth Adams. All rights reserved.