During a recent conversation with a leader of an organization devoted to ending global poverty, he remarked that despite the good work they were doing, they had not gained as much traction as they had hoped. As he listed a variety of changes he wanted to implement, one stood out: He suggested that his group needed to have a T-shirt or bracelet that people could receive for participating, something that would make them feel like part of a group.

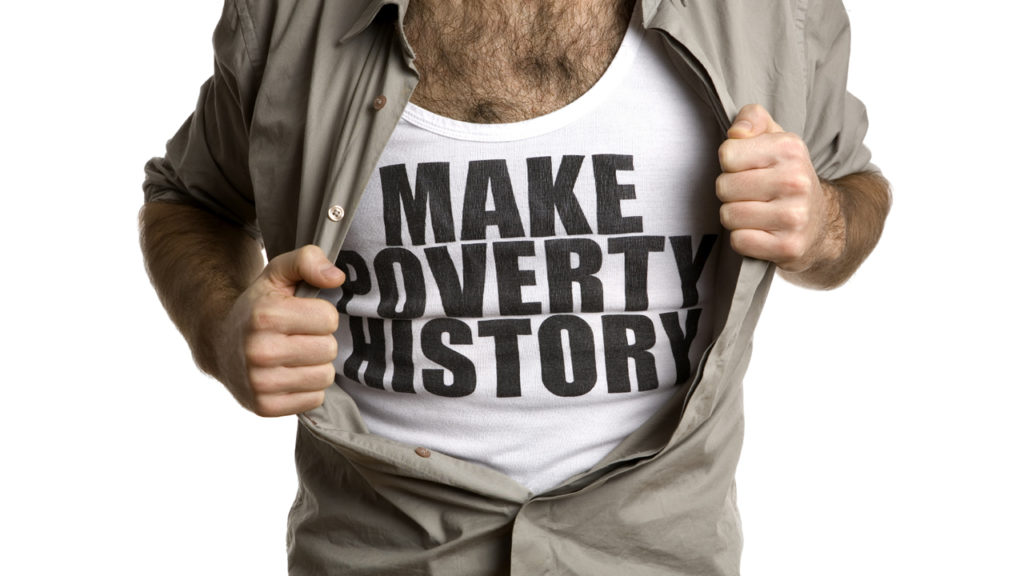

Identifying ourselves with the causes we support is a mainstay of American life. The T-shirt, and more recently the wristband, has become the equivalent of a billboard that allows us to promote and identify with the causes and messages that excite us. Evangelicals had no small part to play in this trajectory — the WWJD bracelet phenomenon launched a thousand derivatives. More recently, Lance Armstrong’s Livestrong sports bracelets made the leap into “iconic” status, a leap that their pervasive use among the celebrity class enabled.

This desire to promote the causes we care about is understandable and has numerous benefits. After all, many social ills are able to remain in part because we are not attentive to them. The cliché that “all that it takes for evil to triumph is for good men to do nothing” is, like many such clichés, a close approximation of the truth that misleads more than it helps. When faced with evil, nothing is precisely what good men do not do (to go for the double negative). The better way of putting it is that evil triumphs when good men remain unaware of it. Secrecy is an ally of injustice as much as it is of virtue, which is why most crime happens in the night. As long as it is invisible to us, injustice will remain.

But in recent years, the desire to “create awareness” around the causes we care about has been married with our purchasing decisions and desires for profit. Choosing what to buy and what to refrain from is an ethical matter — the Fair Trade movement, for instance, arose because activists considered business practices in the developing world unjust and wanted to offer products that were made without dehumanizing or enslaving others. But “conscientious consumption,” as the practice is sometimes called, has morphed into buying products that then donate either goods or a percentage of profits to the needy. Before TOMS Shoes, which has become the most high profile such fusion of making money through doing good for others, Bono’s product (RED) made it possible for consumers to merge their desire to help others with their desire for an iPod.

For both TOMS and (RED), the “cool quotient” has been inseparable from their success. Scarlett Johansson, Charlize Theron and others have brought TOMS into the celebrity style magazines, and no one could dispute the sheer power for (RED) of having Bono as its founder. The fusion of activism, quality products and celebrity appeal are a potent combination that makes for nearly inevitable success. Buy an iPod that’s endorsed by Bono and helps the poor? Who could say “no” to that?

Yet we should put hard questions to this sort of “compassionate consumerism” and the fusion of branding and justice it entails. The effectiveness of such programs for those they claim to help is still an open question, but so is their effect on us.

While injustice may thrive in secrecy, as Christians we are called to seek justice in secret as well. The standard that Jesus establishes in the Sermon on the Mount is so stringent that we should not let our “left hand know what [our] right hand is doing” (Matthew 6:3). At the same time, Jesus instructs us (in the same sermon) to let our light shine before others “so that they may see your good works and glorify your Father who is in heaven” (Matthew 5:16). While there’s a bit of a conundrum here, it seems to make sense that we should do good without promoting the good we are doing, lest we “have [our] reward in full” (Matthew 6:2) in the praise that others give us.

Yet at the same time, even where our “compassionate consumerism” is not the whole of our charitable activity (and it never should be), tying relief for the poor, widow and orphan to acquiring material comforts and creating more wealth through profits risks corroding our charitable efforts by tying them to the benefits we receive. The philosophy of doing good to others through consumption that undergirds the union is, from one standpoint, a subtle variation of prosperity theology. The benefits we receive from doing good are not “crowns in heaven,” but immediate and tangible goods (that really are goods!) that we can enjoy here and now.

Yet the legitimacy of Christian charity should not always be measured by its immediate consequences. “One sows but another reaps” may have a different context (John 4:37), but the principle is true here as well. For Christians, doing justice and evangelism are community projects. The benefits and fruits of any one individual’s efforts may not be readily apparent. Yet the individualistic assumptions of “compassionate consumerism” and the immediately tangible benefits or our purchasing both breed a focus on the short-term results, potentially eroding our long-term will to do good, turning it into a fad that prompts businesses to move on once profits dry up.

In one sense, then, Christian charitable activity should be marked not necessarily by the benefits we receive from it, or even by the immediate effectiveness of the program, but by a willingness to engage in what we might call a “divine wastefulness,” a giving without expectation of return that resembles and imitates the “wasteful” self-giving Jesus on the cross. This sort of giving is no excuse for imprudence or a lack of due diligence. Quite the opposite, in fact, because doing this would inevitably look beyond the short-term benefits of a program to the long-term, structural problems that may require decades of sacrifice with very little “return on investment.” According to my friends in the nonprofit world, this sort of long-term horizon is rather rare among givers. Yet to avoid reducing helping the poor to a trend or a fad, it is precisely that sort of thinking that is required.

Wearing our social causes on our sleeves and wrists may be popular, but as Christians we should reflect carefully about whether it goes against the grain of God’s kingdom. Our love for our neighbor may require creating awareness about their plight. But charity is more than that, and merging our giving with consumer desires creates challenges that require careful sorting through. The desire to be a part of a movement is strong, so strong that the marketing madmen and women have begun to use it for their own ends. As Christians, we need to ensure that if we are wearing our social justice on our sleeves and wrist, it is accompanied by the love, joy and peace that mark us off as the people of the Triune God.

Copyright 2011 Matthew Anderson. All rights reserved.