Several years ago, as a teenager volunteering with a missions organization, I sat down in a double-wide trailer-turned-sanctuary to hear a guest from India. I don’t remember his name or his subject matter, but I remember this: Casting his eye disapprovingly on those of us who hadn’t come prepared, he demanded, “Why don’t you have your Bibles?”

As we looked at one another, discomfited, he continued. “You must always bring your Bibles to church. Otherwise, how will you know what I’m telling you is really what it says?”

That Indian brother had no intention of misleading us, of course. If all is as it should be, the pastors and elders in your life intend to tell you the truth. But the fact remains that we are all human and that we live in age of biblical illiteracy — even in the church. That preacher’s words sparked a change in the way I approach the Word of God, especially in corporate contexts. I’ve become a pulpit critic.

Being a pulpit critic isn’t about taking the preacher apart, any more than being a book or movie critic is about indiscriminately bashing every work you see. It’s about engaging, exploring and getting past the surface of things. The greatest danger is not that we won’t hear truth from the pulpit, but that we’ll simply accept it without thought or personal application and that we’ll survive on a diet of pre-packaged spirituality instead of wrestling with the Scriptures as we ought.

In ancient Israel, the common people relied on priests and prophets to pass on messages from God. Under Christ, however, things have changed:

But ye are a chosen generation, a royal priesthood, an holy nation, a peculiar people; that ye should shew forth the praises of him who hath called you out of darkness into his marvellous light” (1 Peter 2:9, KJV).

Today, every believer is a priest with direct access to God. Most of us are literate and own at least one Bible. If I go to church every week and simply absorb messages instead of actively engaging with them — reading along, thinking critically, asking questions to follow up later in study and prayer — then I have nothing but my own laziness to blame if my knowledge of truth remains shallow.

I didn’t “get” that Indian preacher’s words for quite a few years. In that time I unwittingly discovered how many things are regularly preached with the best of intentions that are not really in the Bible. I grew more and more inundated with extra-scriptural ideas that I thought were truth. They challenged and moved me; they came from well-meaning people. Eventually, though, I crashed. Truth and fiction collided and left me close to spiritual shipwreck. My understanding only went knee-deep, and I needed something I could swim in. Only then did I start looking to see if what I was told was “really what it says.”

Four habits have changed my Sunday mornings from an exercise in sitting to an exercise in seeking.

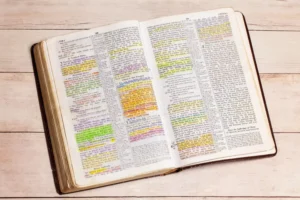

Keep an Open Bible

The first habit is the most obvious: the one on which I was challenged years ago. Always bring your Bible to church. Don’t use the one in the back of the pew — use your Bible, the one you know inside out (or want to know inside out!). Open it. Look up every verse the pastor references. Otherwise, how will you know what it really says?

Take Notes

There are several ways to do this. The most obvious is to follow the bullet points on the Sunday morning Power Point. These notes will send you home with a basic summary of the pastor’s message.

My notes are a bit different. You could call mine “exploration notes.” I write down things that stick out to me in the text even though the pastor didn’t focus on them. I write down surrounding verses or other bits of Scripture that apply. I write thoughts on what the pastor is saying. Sometimes I write prayers. Chiefly, I write a lot of questions. If I disagree with it, if I’m not sure about it or if I just want to learn more, it goes into the notes. I did this recently and have a host of notes on the role of the Spirit that I can hardly wait to follow up. “Light is sown for the righteous,” says David in Psalm 97:11, and we get the joy of harvesting it.

Question Platitudes

“Hate the sin, love the sinner.”

“God helps those who help themselves.”

“Christ calls us to take up our cross and die to ourselves.”

“If you want to be saved, surrender your life to God.”

Christianity has its own host of catch phrases. Some are true; some are not. None of the above four sentences are actually in Scripture — not in those exact words. Platitudes can be great thought-starters, because they weren’t stale when they were first spoken. Someone looked at a whole bunch of Scripture, crunched it down and tried to state the essence of it. Maybe that someone was right, maybe not. Either way, we can learn a lot by picking platitudes apart and trying to figure out how they really line up with Scripture. Retrace the journey, and see if you reach the same destination.

Examine Context

Taking a Scripture out of context is like trying to understand a fish without understanding water. Conversely, examining the context of a verse can open whole new worlds of truth. If you’re listening too closely to read the context in church, read it when you get home. Look at what’s really being said. John Wycliffe said it well:

It shall greatly help you to understand Scripture, if you mark not only what is spoken or written, but of whom, and to whom, with what words, at what time, where, and to what intent, with what circumstances, considering what goes before and what follows.

Use the Sermon as a Jumping-Off Point

Church is meant to be an experience of community and an encouragement to your spiritual life. It is not the focal point of faith, and listening to a sermon once a week does not exempt any of us from studying the Word ourselves. I’ve found that the pulpit gets me thinking in new directions and presents a lot of things I want to study on my own. This is the kind of relationship that should exist between pastor and congregation: the kind that leads to growth and maturity.

Roger Thoman of House Church Blog writes,

Give me an outstanding … spiritual message. In fact, give it to me from someone who has delved deeply into the things of God. Give me a message that has come from that person’s diligent meditation on the Word of God and well-disciplined labor in the things of God. Then take that powerful message and wrap it up in a 30-minute sermon and serve it to me on an easy-to-reach platter so that I can feed on it quickly and easily.

And there is the problem.

The message may, indeed, come from someone’s deep intimacy with God and loving labor in God’s Word. But I will not be able to digest that message, no matter how well prepared it is, unless I am, myself, putting forth my own effort to draw close to God and know Him. There are no shortcuts to actually grasping hold of the things of God. We can hear the messages, and even be emotionally charged and thrilled by them, but transformation that leads to more deeply knowing God comes only by our own time spent in pursuit of Him.

In looking to see “what’s really there,” we shouldn’t be driven by pride or a critical spirit. Instead, eagerness to know God and seek truth should be our primary motivation. Becoming a pulpit critic shouldn’t make you a pastor’s worst nightmare, but the fulfillment of his role. We need to take what we hear seriously enough to follow it up.

Engage with the truth — though its teachers are human, it is divine, and truth only will set us free.

Copyright 2007 Rachel Starr Thomson. All rights reserved.