In May 1943, German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote a letter to a young bride and groom, advising them on the nature of the union they were about to enter:

Your love is your own private possession, but marriage is more than something personal — it is a status, an office. Just as it is the crown, and not merely the will to rule, that makes the king, so it is marriage, and not merely your love for each other, that joins you together in the sight of God and man. As you gave the ring to one another and have now received it a second time from the hand of the pastor, so love comes from you, but marriage from above, from God. As high as God is above man, so high are the sanctity, the rights, and the promise of love. It is not your love that sustains the marriage, but from now on, the marriage that sustains your love.

While his counsel is powerful, the truly compelling part of this story begins when we consider where this letter was written, and who was doing the writing. This was no sunshine musing from a mere relationship counselor, but a wedding sermon offered from a prison cell, written by a hero waiting for the inevitable day of his painful execution.

This is a story about faithfulness, holiness, and sacrificial love.

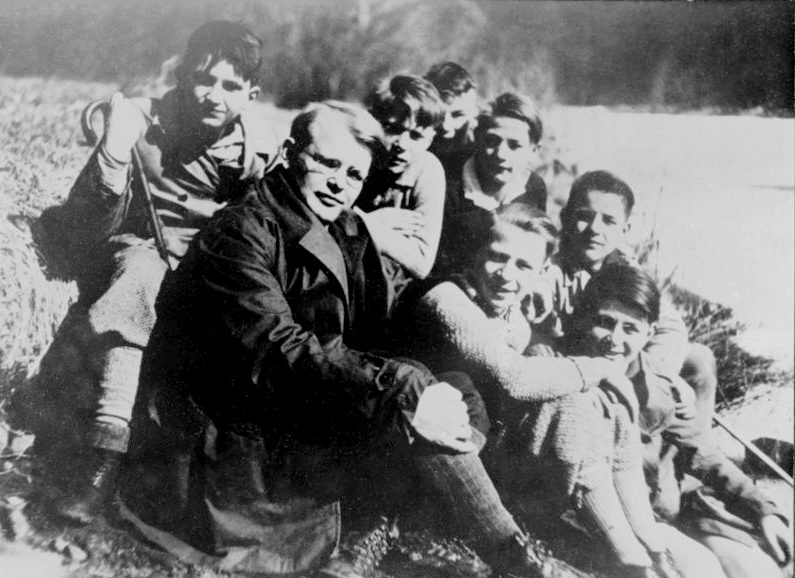

Dietrich Bonhoeffer was born on Feb. 4, 1906, in Breslau, Poland. In a family of 10, his parents taught Dietrich the foundational principles of Christian humanism from an early age. By the time he was 14, he chose a path of theological study; at 18, he was learning from the teachers of the day in Berlin; and at 24, he was lecturing in their stead.

As an academic and a pastor, Bonhoeffer impressed the wise men of his era. At Union Theological Seminary in America and at Chichester in Britain, he endeavored to explain the plight of the German Church and the need for ecumenical revival. His message inspired and moved people, who lent help to his underground Christian training college in Germany.

When it became clear that war was coming to his land, Bonhoeffer’s friends urged him to leave Germany, or risk imprisonment and death. For a time, he listened, and came to New York prior to the outbreak of World War II. Yet as Bonhoeffer walked around the streets of the city, he became convinced that, like Jonah fleeing from Nineveh, he had refused the call of God to fight the Nazis from within Germany. And he knew what that call meant — after all, as he once wrote: “When Christ calls a man, He bids him come and die.”

So Bonhoeffer boarded a ship and sailed back toward his homeland and his doom.

He was conflicted about his role as a Christian caught in the horror of Nazi Germany. The state had engulfed and bent the church, as an entity, to its will. The church leadership was made up of men compromised, helpless, or serving as willing participants. And those church leaders who spoke out against the villainy pre- and post-Kristallnacht were either brutally murdered or sent to concentration camps.

Bonhoeffer and his allies could not abandon their fellow Christians in Germany. They made the decision to act, as members of a faith-based resistance, to do whatever they could in this horrible situation. As Bonhoeffer described it:

[T]here are three possible ways in which the church can act toward the state: the first place, as has been said, it can ask the state whether its actions are legitimate and accordance with its character as state; i.e., it can throw the state back on its responsibility. Second, it can aid the victims of any ordering of society, even if they do not belong to Christian community — “Do good to all people.” In both these courses of action, the church serves the free state in its free way, and at times when laws are changed the church may in no way withdraw itself from these two tasks. The third possibility is not just to bandage the victims under the wheel, but to jam a spoke in the wheel itself.

Bonhoeffer was still, at root, an avowed pacifist. But while he worked in peaceful ways as a double agent of the Nazis, helping 14 Jews escape from Germany, he knew that work was insufficient. He refused to be a silent witness — so he and his allies began to aid the efforts of the German resistance to assassinate Hitler. Faced with the greatest evil of the modern age, they committed themselves to jamming a spoke in the wheel of the state.

Could it be right for a Christian to kill an evil man in the defense of others? Bonhoeffer could not reconcile his non-violent beliefs and the calling of the church to worship God and minister to mankind on this earth with his desire to end another’s life — even if it was the life of a vile murdering dictator.

Yet he also knew that God calls us to work His will, not ours; he knew that God grieved for His children, and that the place of the Christian is by God’s side. Christ is the Lamb of God, who comes to take away the sins of the world. But He is also the Lion of Judah, who sits at the right hand of the Father in heaven, and who will come again in glory to judge the quick and the dead. He is not a non-divisive figure — He comes not to bring the conflict between good and evil to a diplomatic solution, but to a final resolution. C.S. Lewis’ dictum still holds: the Christ is not a tame lion.

Ultimately, Bonhoeffer recognized this truth. As a double agent, he was familiar with Hitler’s works — he knew the true degree of Nazi atrocities long before the rest of the world did. And he believed that the only way of stopping the Reich was by undertaking a mission that would require him to aid in the shedding of another man’s blood. He was convinced that doing any less would be to fail in loving his suffering neighbors.

So Bonhoeffer labored to end the war and the Holocaust. It is in that labor that he was arrested, jailed, and eventually executed — in April 1945, one last casualty of a dying, desperate Reich, stabbing from hell’s heart. We have his letters and his writings from prison thanks to the respect shown by his guards — who could not help but recognize the small man who stood as a giant.

Bonhoeffer’s decision, as emotionally wracked as it was, remains a fundamentally righteous position. There will always be evil men, and there will always be good men. For both, it is up to God to judge their salvation or damnation. But do not allow yourself to believe that He stands neutral between them. Consider John 3:

For God did not send the Son into the world to judge the world, but that the world might be saved through Him. He who believes in Him is not judged; he who does not believe has been judged already, because he has not believed in the name of the only begotten Son of God. This is the judgment, that the Light has come into the world, and men loved the darkness rather than the Light, for their deeds were evil. For everyone who does evil hates the Light, and does not come to the Light for fear that his deeds will be exposed. But he who practices the truth comes to the Light, so that his deeds may be manifested as having been wrought in God.

Bonhoeffer made the right choice. He took the ship back to his Ninevah. Had he taken it to the success he imagined, we might remember him today as a man of God who averted the greatest tragedy in the history of modern man. He took that ship instead to martyrdom, to the concentration camp, to the grave. But God did not forsake him, even in death. As Bonhoeffer wrote from the jail: “A prison cell, in which one waits, hopes … and is completely dependent on the fact that the door of freedom has to be opened from the outside, is not a bad picture of Advent.”

When it comes to our attitude toward marriage and the call to love our neighbor, the lesson Bonhoeffer has for us is not an easy one. It’s a lesson that Christian marriage cannot serve as a haven from the outside world or a justification to set aside the duties of faith. It’s a lesson of the enormous responsibility of a union of two souls to display the sacrificial love of Christ. We cannot underestimate the power of two hearts, united in faithfulness to one another, to minister to a fallen world, a sentiment to which Bonhoeffer pointed us:

Marriage is more than your love for each other. It has a higher power, for it is God’s holy ordinance, through which He wills to perpetuate the human race until the end of time. In your love you see only your two selves in the world, but in marriage you are a link in the chain of the generations, which God causes to come and to pass away to His glory, and calls into His kingdom. In your love you see only the heaven of your own happiness, but in marriage you are placed at a post of responsibility towards the world and all mankind.

Copyright 2006 Ben Domenech. All rights reserved.